The buildings around which i grew up are being redeveloped (except my own) eclipsing a precious small compound which bore me like my own mother. The developer vacates the buildings and encloses the compound in a wall, the building walls are now punctured gaping holes with balcony windows stripped of glass and grill and bring to my mind personal memories of laughter and joy, little sorrows and the patter of so many children's naked feet on flagstones around the compound, invoking deeply hidden memories stashed away like jewels in a granny's wooden box. This write up is just a recollection of some of those times. Read it if you wish and have the time to revisit the past. A lament if you may.

I remember as a child that i was astonished when i read the poem "My parents kept me from children who were rough"*. I remember reading it several times at school how did the author Stephen Spender so vividly capture my own predicament of wanting to play and befriend the teeming hordes of children who kept the compound filled with play, laughter, shouts and cries all hours of the day but whom i alas could not join. For i was given to books, and studies that my parents thought were priorities more important than play (how wrong they were!). But oft would i sneak up to the window and longingly, sometimes with tears watch the rambunctious play of the several children who lived around the compound. I was however never part of any gang, quite unskilled at any game, frail, often ill, odd with a large head on an darkly emaciated frame, nicknamed "Kalia" that i always resented. Yet that was the name i was given and it seemed that Mushi my neighbour was often the one who kept these names and reminded others of their caricature ( I remember "Maakad Bindu" as another uncharitably given to another). Those who had elder aggressive brothers were often spared of such iniquities. Alas Mushi is now no more and time silenced his endless pranks and constant mischief. I would easily get hurt and bruised even at simple games and soon had to find gentler avenues to slake my curiosity and play. My exaggerated sense of age made me feel that boys who were older than me were excessively so and those younger even more so; the Goldilocks friendship i longed for never emerged. I often played with girls ( it was with Tanuja for long that i payed just below her window sill- as my mother apologetically explained that she never hit me like the others) at their homely imaginative interiorised spaces and gentle reprimands, or scavenging trinkets behind the building, or playing simpler games where competitiveness and combat were not essential. But i longed to belong to the rough and tumble of the increasingly dangerous games that growing children were wont to play. My favourite bundle of mischief was Shankar dubbed "Dedh Foot" for his short stature by Mushi which nonetheless could barely contain the immense reserves of energy expended at play at all hours of the day or even night, for neither time nor weather could rein him indoors. Yet oft did i complain bitterly to his mother that i was hit by him at play, though the very next day i would search him out again for a new adventure and even digging a hole in the ground was an adventure. Alas he too is no more among us as the gods too wished to play with him.

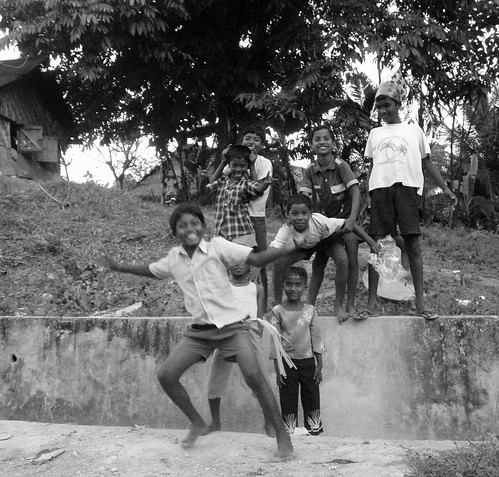

I particularly envied the homes where there were several siblings at home who did not need to go out to commence play and home was merely another extension of the compound. There were the Kates, the Pillais, the Balu siblings, the Johnsons the Nambiars the Menons, Kamaths all home teams. Many of them had someone or the other outside all the time obsessively at play. I lamented my own return home each evening from strictly measured doses of play when i dragged my feet to a studious ambiance filled with the drudgery of study homework or works of edification. Never again did the compound see so much laughter, play and merriment in its small enclosure as those days in the late sixties unto the early eighties. The very earth laughed a deep red in its ochre soil and trees and shrubs bloomed to embrace us into their dense shrubbery promising to keep our tender secrets. Each season brought an endless procession of games many of which are no longer played, 'lagori' 'sakhli', 'kho-kho', 'kabbadi', 'gilli danda' 'langadi' hide and seek in an endless inventiveness of rules that were always broken to raise voices in fight. The establishment games like cricket, football, hockey, volley ball, badminton were also there most of which i was very bad at and gave up trying. Festivals like Holi, Divali, New Year, etc were long duration occasions for even more merriment and the lengthy school holidays never seemed to end. Every stick, stone brick or wall would be objects to be used at play ingenious and imaginative. Scaling walls, breaking into gardens, plundering raw fruit like monkeys, and leaving trails of devastation were quotidian. Climbing terrace tanks and even falling off them four floors into the garden were commonplace. Sending fireworks into homes and burning their bedrooms were a speciality of only a few though, spectacular though they seemed. Endless fights and quarrels, swollen limbs, torn shirts, loose pants that slipped to reveal the tiny bottoms, scratches, fractures, black eyes where even parents sometimes intruded were a daily occurrence. It looked like we were especially blessed as children of every size, shape, stature, gender, temperament, language, background were in abundant supply as though it were the very cradle of fertility. The rains were bountiful and rainbows bent close and summer clouds seemed to hang low and slow begging the sun to be gentle. We could see the horizon and Sion in the distance and marvel at its fort and stare at the flares that the RCF factory would burn each evening.

All the gaiety made the gods envious as they conspired to make naughty elves into gawky teens, huddled to form secret bands that swore, used invective and expletives to show their marginal masculinity that sprouted around tender lips, smoked, drank, and bragged their imaginary exploits. Neighbours forgot to close their doors as the traffic never ceased in many homes and thefts were relatively unknown. But such concourse and chatter eventually brought forth also petty fights often over children which were soon forgotten. Growth did seem to descend rather quickly on this gaggle. I remember a gawky kid who would sing taans while flying his kite which he was good at (I gave up trying). He would bashfully and solemnly take his carefully hand drawn 'Saraswati' on a slate to his tin shed school Abhinav Sahakar for worship. He would come home to my brother to solve some intractable math problem before exams. His favourite songs were from Madhuvanti. Today i cannot recognise him as I search him beneath his successful career as a handsome actor. As I look up at the corner flat of the opposite building facing the road the holes in the wall seem like vacant eyes who had seen much. i still see the heads of four children Nannu, Gopan, Kiran and Vasant graded in height mischievously plotting some fun activity which i could never join, shouting down instructions to their gang below. I envied such a troop at home always at play unlike my own rather studious brother. Our Hindi teacher Tripathi sir once strung their names into a sentence "Vasant ki Kiran jab Narayan par girti hai to Gopal bansi bajata hai" though this sounds like doggerel now, i envied their play like otters on the Ganges. I also remember the families where the grim reaper cruelly seized the father early to these children in at least three homes and the vigils their mothers kept, and sobs they muffled within struggles as their children wondered about their fate. I also remember how an elderly bachelor somewhat odd who threw chocolates from his third floor flat at squealing children who thought the heavens opened up until his own marriage sobered him up; alas he too is no more. There were those fathers like Mr Aginswar whose punctual arrival every evening at 5.00 pm would announce to ladies to adjust their clocks and give children their signal to run down. His arrival meant play time. I remember with much amusement when as children we spoke conspiratorially about Mr Burte being a Communist and not having the foggiest idea what it meant or wondering about an elderly gentleman who spoke of Manduky Upanishad under the influence of a drink. There was an old man draped in a dark woolen blanket like Baba Kali Kamliwala who would be chased by amused children as he swore at them, there was another lady who held dainty kitty parties (and we drooled wondering what was on the menu). We saw ghosts in uninhabited flats and threw stones to deter their haunt. We were scared of unlit staircases and saw ghouls perched atop fused bulbs and near terrace doors (where we would sneak to without telling mom). We fished for tadpoles and small fish in the gutters holding our catch in tiny bottles, held earthworms between fingers, teased lizards by cutting their tails, chased sparrows which seemed to be always so many around, tied strings to dragon fly tails or tin cans to dog tails. We dug for gold finding coloured bits of glass or shell that we treasured. We collected feathers and leaves dried flowers between books that we forgot about and told secrets to everyone.

Then there was the Indo Pak war and they seemed such fun times as we doubled up as soldiers during day in mock fights where we became both Indian and Pakistani soldiers in turns (everyone wanted to be on the Indian side) and hidden under the bed chuckling loudly asking mom whether it was safe to emerge upon hearing the sirens announcing curfew. We would joyously abandon homework or studies armed with a good excuse for school the next day and reluctantly helped dad in his elaborate work of covering all window panes with cardboard so that light never filtered out during curfew and alas our short lived exemption from homework would dry up. Earthquakes and even fires or blackouts and power outages were fun occasions as we would all run down ahead of our parents into our dear compound and use the excuse to play in the darkness and often wished there were more earthquakes or even wars. Heavy rains and natural calamities brought smiles upon our faces as our parents were busy with more important things than concentrating on us and excused us from school. We would not even open our school bags that day; and those bags had nothing precious except our favourite pencil boxes and compass, coloured stones, half eaten biscuits, chocolate wrappers, cut pictures all crumpled up, magnets, toy parts and pencil stubs worn down and pieces of perfumed erasers. I remember with horror when my friend threw his school bag out the moving school bus window because a banana (we never knew how many anana's were there in the spelling banana) was crushed by the school books and smeared all over ( his poor mother had to retrace those steps and retrieve what she could). Sometimes they even showed us children edifying or Hindi feature films in the compound as we huddled close, mouths wide open lost in the story (i remember closing my eyes tight during all the fight sequences), oblivious to insects and mosquitoes or other children clambering over us. In the monsoon when the compound was slushy though inviting we were forbidden by mothers exasperated at dirty feet to play in the mud but then took to the wide roads that had scarce traffic. The compound was our vast stretch of earth under clear blue skies and cottony clouds we needed nothing else. It was our refuge, the ground beneath our tiny feet. Even going home to eat our meals was an interruption unless of course our nose led us to the fragrance of fried savouries or sweets from some kitchen.

The most daring of siblings were the Kate brothers who no danger would deter whether wading through dark swampy waters, hacking mangroves, catching swamp and garden snakes and killing them and displaying them as proud trophies, holding lizards in their palms, they were a trio who seemed invincible and also fearful. They seemed to attract all the bigger boys or even my own brother. My brother of course was different, he was a nerd of nerds always buried in his school books, preparing for exams months before they would even commence. He would not play and neither would he allow me to. When i see any of them i cant relate that they were the same kids. They seemed enormous powerful and huge and fearful to my childish eyes. Today when i relate to some of them i feel they are not the same. They have had some evil spell cast on them to shrink them into tame cats than the prowlers I imagined them to be. Some of the boys who were siblings to these were cut of a different cloth i thought as they seemed to be gentler though i now realise that being elder to them they probably defered to age (though the rough and tumble of their play was no less frightening to me). Many whose names i barely remember. One even became my student as i was his department head and subject instructor for the two years he did his MBA. Children i believe make a narcissism of minor difference in age. I was too young for some and too old for the rest never one among them. There were others fringe players like myself probably equally shy and aloof one who had huge stashes of comics which i would either borrow or steal and furtively read between the covers of my school texts (until my brother discovered them and tore them up). And we had so many characters not just from Enid Blyton (long before Golliwogs were decidedly racist) but Phantom, Mandrake, Tarzan, Casper, Sad Sack, Spooky, Archie, Hot Stuff, Little Lotta, Blondie, Asterix and Tin Tin, pixies, gnomes, elves, leprechauns, fairies, and those from Chandamama and Amar Chitra Katha all more valuable than greenbacks. As we grew older and rebelled as teens in our inimitable ways getting away to talk in whispers of taboos like sex or drinking or practicing bad words to be uttered with insouciance. I horrified my parents by becoming deeply religious and reading books not congenial for my age. The girls banded together in their own small groups, though the elder of them were seemingly distant probably imagining futures not yet upon our little minds. Many boys held their secret crushes and bated breath and silly tales and catcalls. Most of these children unlike myself and my brother and few others went to the same school Cardinal Gracias and i used to complain to God how unfair he was to me that not only these guys constantly play at home and in the compound but on the way to and fro and at school too. They carried their secrets together and i was privy to none of them. I wish it were a perfect idyll and alas it wasn't as domestic strife and violence was rife and children often huddled incomprehensibly as their elders swore or fought both at home and outside.

I grew to be uneasy and restless and I severed the already tenuous links with my cohort of children and came to see my new identity as some one different, serious about purpose and meaning and much prattle that alarmed my onlookers (and intrigued Mahesh Kamath to be my sole friend who like' Hobbes' would listen to my gibberish endlessly as we worked up being the Asiatic Society, Lalit Kala and Sahitya Akademi, Krishnamurthi Foundation all rolled into one). I wore conservative apparel like dhoties and kurtas while the rest sported torn jeans. I worried my parents no end with what they thought was the worst of both worlds. My migration to another state for my engineering studies cut loose all connections and probably helped me grow up unfettered by my own past for the better or the worse. On my return after many years it was never the same again and what was broken and torn could never be mended or stitched back. The compound was paved over and concrete poured around and prosperity converted much of what remained of the compound to a parking lot with a little strip pretentiously called Fulvari where they placed most unimaginatively a swing and slide that rusted into oblivion making tetanus stained gashes to children who ventured. Most of the sibling brothers had departed, they punctuated their routines with scheduled visits to parents that seem sometimes a solemn routine not always joyous or siblings, sometimes close some distant, some torn by rivalry some keeping up appearances. I was a stranger in my own home not just compound and fled to the solace of the unfamiliar. Decades later when my father persuaded me to return i came to see the trees grow older, ailing and in some cases decrepit or even dead. Each carefully treasured their memories of home and hearth that the compound foregrounded, the laughter and the tears secretly. They spoke of redevelopment in a tongue that i scarcely understood (or wished to understand); of swimming pools and swanky lots and whether they should have one or two parking spaces. They knew not the secrets of the compound or its million hiding places, of boughs that bore our weight without breaking, the secret signs and codes and the million ties that compound held our hands by in our mud smeared faces and slipping 'chuddies'.

Never again have i seen a train of such wonderful children so full of life and joy blessed by nature in her ample arms play again in that compound. I feel sorry and pity for children in the same compound who today seem to play sterile games restrained by their finery and upbringing to be the child nature wants them to be. The compound is now cut up by the developer. The walls are pulled down, the windows stripped of their happy faces and robbed of their memories. The trees forlorn and sad, the birds mournful. As i see the compound walled up with tin sheets i regret that the ringing shouts, of children will never bedeck the gardens and the grounds, never beckon us back again into that innocence and simplicity where there was much contentment. In the words of the poet

I feel like one who stands alone,

Some banquet hall deserted,

Whose lights have fled,

Whose garlands dead,

And all but he departed.

_________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

*My parents kept me from children who were rough

and who threw words like stones and who wore torn clothes.

Their thighs showed through rags. They ran in the street

And climbed cliffs and stripped by the country streams.

I feared more than tigers their muscles like iron

And their jerking hands and their knees tight on my arms.

I feared the salt coarse pointing of those boys

Who copied my lisp behind me on the road.

They were lithe, they sprang out behind hedges

Like dogs to bark at our world. They threw mud

And I looked another way, pretending to smile,

I longed to forgive them, yet they never smiled.

Stephen Spender

I remember as a child that i was astonished when i read the poem "My parents kept me from children who were rough"*. I remember reading it several times at school how did the author Stephen Spender so vividly capture my own predicament of wanting to play and befriend the teeming hordes of children who kept the compound filled with play, laughter, shouts and cries all hours of the day but whom i alas could not join. For i was given to books, and studies that my parents thought were priorities more important than play (how wrong they were!). But oft would i sneak up to the window and longingly, sometimes with tears watch the rambunctious play of the several children who lived around the compound. I was however never part of any gang, quite unskilled at any game, frail, often ill, odd with a large head on an darkly emaciated frame, nicknamed "Kalia" that i always resented. Yet that was the name i was given and it seemed that Mushi my neighbour was often the one who kept these names and reminded others of their caricature ( I remember "Maakad Bindu" as another uncharitably given to another). Those who had elder aggressive brothers were often spared of such iniquities. Alas Mushi is now no more and time silenced his endless pranks and constant mischief. I would easily get hurt and bruised even at simple games and soon had to find gentler avenues to slake my curiosity and play. My exaggerated sense of age made me feel that boys who were older than me were excessively so and those younger even more so; the Goldilocks friendship i longed for never emerged. I often played with girls ( it was with Tanuja for long that i payed just below her window sill- as my mother apologetically explained that she never hit me like the others) at their homely imaginative interiorised spaces and gentle reprimands, or scavenging trinkets behind the building, or playing simpler games where competitiveness and combat were not essential. But i longed to belong to the rough and tumble of the increasingly dangerous games that growing children were wont to play. My favourite bundle of mischief was Shankar dubbed "Dedh Foot" for his short stature by Mushi which nonetheless could barely contain the immense reserves of energy expended at play at all hours of the day or even night, for neither time nor weather could rein him indoors. Yet oft did i complain bitterly to his mother that i was hit by him at play, though the very next day i would search him out again for a new adventure and even digging a hole in the ground was an adventure. Alas he too is no more among us as the gods too wished to play with him.

I particularly envied the homes where there were several siblings at home who did not need to go out to commence play and home was merely another extension of the compound. There were the Kates, the Pillais, the Balu siblings, the Johnsons the Nambiars the Menons, Kamaths all home teams. Many of them had someone or the other outside all the time obsessively at play. I lamented my own return home each evening from strictly measured doses of play when i dragged my feet to a studious ambiance filled with the drudgery of study homework or works of edification. Never again did the compound see so much laughter, play and merriment in its small enclosure as those days in the late sixties unto the early eighties. The very earth laughed a deep red in its ochre soil and trees and shrubs bloomed to embrace us into their dense shrubbery promising to keep our tender secrets. Each season brought an endless procession of games many of which are no longer played, 'lagori' 'sakhli', 'kho-kho', 'kabbadi', 'gilli danda' 'langadi' hide and seek in an endless inventiveness of rules that were always broken to raise voices in fight. The establishment games like cricket, football, hockey, volley ball, badminton were also there most of which i was very bad at and gave up trying. Festivals like Holi, Divali, New Year, etc were long duration occasions for even more merriment and the lengthy school holidays never seemed to end. Every stick, stone brick or wall would be objects to be used at play ingenious and imaginative. Scaling walls, breaking into gardens, plundering raw fruit like monkeys, and leaving trails of devastation were quotidian. Climbing terrace tanks and even falling off them four floors into the garden were commonplace. Sending fireworks into homes and burning their bedrooms were a speciality of only a few though, spectacular though they seemed. Endless fights and quarrels, swollen limbs, torn shirts, loose pants that slipped to reveal the tiny bottoms, scratches, fractures, black eyes where even parents sometimes intruded were a daily occurrence. It looked like we were especially blessed as children of every size, shape, stature, gender, temperament, language, background were in abundant supply as though it were the very cradle of fertility. The rains were bountiful and rainbows bent close and summer clouds seemed to hang low and slow begging the sun to be gentle. We could see the horizon and Sion in the distance and marvel at its fort and stare at the flares that the RCF factory would burn each evening.

All the gaiety made the gods envious as they conspired to make naughty elves into gawky teens, huddled to form secret bands that swore, used invective and expletives to show their marginal masculinity that sprouted around tender lips, smoked, drank, and bragged their imaginary exploits. Neighbours forgot to close their doors as the traffic never ceased in many homes and thefts were relatively unknown. But such concourse and chatter eventually brought forth also petty fights often over children which were soon forgotten. Growth did seem to descend rather quickly on this gaggle. I remember a gawky kid who would sing taans while flying his kite which he was good at (I gave up trying). He would bashfully and solemnly take his carefully hand drawn 'Saraswati' on a slate to his tin shed school Abhinav Sahakar for worship. He would come home to my brother to solve some intractable math problem before exams. His favourite songs were from Madhuvanti. Today i cannot recognise him as I search him beneath his successful career as a handsome actor. As I look up at the corner flat of the opposite building facing the road the holes in the wall seem like vacant eyes who had seen much. i still see the heads of four children Nannu, Gopan, Kiran and Vasant graded in height mischievously plotting some fun activity which i could never join, shouting down instructions to their gang below. I envied such a troop at home always at play unlike my own rather studious brother. Our Hindi teacher Tripathi sir once strung their names into a sentence "Vasant ki Kiran jab Narayan par girti hai to Gopal bansi bajata hai" though this sounds like doggerel now, i envied their play like otters on the Ganges. I also remember the families where the grim reaper cruelly seized the father early to these children in at least three homes and the vigils their mothers kept, and sobs they muffled within struggles as their children wondered about their fate. I also remember how an elderly bachelor somewhat odd who threw chocolates from his third floor flat at squealing children who thought the heavens opened up until his own marriage sobered him up; alas he too is no more. There were those fathers like Mr Aginswar whose punctual arrival every evening at 5.00 pm would announce to ladies to adjust their clocks and give children their signal to run down. His arrival meant play time. I remember with much amusement when as children we spoke conspiratorially about Mr Burte being a Communist and not having the foggiest idea what it meant or wondering about an elderly gentleman who spoke of Manduky Upanishad under the influence of a drink. There was an old man draped in a dark woolen blanket like Baba Kali Kamliwala who would be chased by amused children as he swore at them, there was another lady who held dainty kitty parties (and we drooled wondering what was on the menu). We saw ghosts in uninhabited flats and threw stones to deter their haunt. We were scared of unlit staircases and saw ghouls perched atop fused bulbs and near terrace doors (where we would sneak to without telling mom). We fished for tadpoles and small fish in the gutters holding our catch in tiny bottles, held earthworms between fingers, teased lizards by cutting their tails, chased sparrows which seemed to be always so many around, tied strings to dragon fly tails or tin cans to dog tails. We dug for gold finding coloured bits of glass or shell that we treasured. We collected feathers and leaves dried flowers between books that we forgot about and told secrets to everyone.

Then there was the Indo Pak war and they seemed such fun times as we doubled up as soldiers during day in mock fights where we became both Indian and Pakistani soldiers in turns (everyone wanted to be on the Indian side) and hidden under the bed chuckling loudly asking mom whether it was safe to emerge upon hearing the sirens announcing curfew. We would joyously abandon homework or studies armed with a good excuse for school the next day and reluctantly helped dad in his elaborate work of covering all window panes with cardboard so that light never filtered out during curfew and alas our short lived exemption from homework would dry up. Earthquakes and even fires or blackouts and power outages were fun occasions as we would all run down ahead of our parents into our dear compound and use the excuse to play in the darkness and often wished there were more earthquakes or even wars. Heavy rains and natural calamities brought smiles upon our faces as our parents were busy with more important things than concentrating on us and excused us from school. We would not even open our school bags that day; and those bags had nothing precious except our favourite pencil boxes and compass, coloured stones, half eaten biscuits, chocolate wrappers, cut pictures all crumpled up, magnets, toy parts and pencil stubs worn down and pieces of perfumed erasers. I remember with horror when my friend threw his school bag out the moving school bus window because a banana (we never knew how many anana's were there in the spelling banana) was crushed by the school books and smeared all over ( his poor mother had to retrace those steps and retrieve what she could). Sometimes they even showed us children edifying or Hindi feature films in the compound as we huddled close, mouths wide open lost in the story (i remember closing my eyes tight during all the fight sequences), oblivious to insects and mosquitoes or other children clambering over us. In the monsoon when the compound was slushy though inviting we were forbidden by mothers exasperated at dirty feet to play in the mud but then took to the wide roads that had scarce traffic. The compound was our vast stretch of earth under clear blue skies and cottony clouds we needed nothing else. It was our refuge, the ground beneath our tiny feet. Even going home to eat our meals was an interruption unless of course our nose led us to the fragrance of fried savouries or sweets from some kitchen.

The most daring of siblings were the Kate brothers who no danger would deter whether wading through dark swampy waters, hacking mangroves, catching swamp and garden snakes and killing them and displaying them as proud trophies, holding lizards in their palms, they were a trio who seemed invincible and also fearful. They seemed to attract all the bigger boys or even my own brother. My brother of course was different, he was a nerd of nerds always buried in his school books, preparing for exams months before they would even commence. He would not play and neither would he allow me to. When i see any of them i cant relate that they were the same kids. They seemed enormous powerful and huge and fearful to my childish eyes. Today when i relate to some of them i feel they are not the same. They have had some evil spell cast on them to shrink them into tame cats than the prowlers I imagined them to be. Some of the boys who were siblings to these were cut of a different cloth i thought as they seemed to be gentler though i now realise that being elder to them they probably defered to age (though the rough and tumble of their play was no less frightening to me). Many whose names i barely remember. One even became my student as i was his department head and subject instructor for the two years he did his MBA. Children i believe make a narcissism of minor difference in age. I was too young for some and too old for the rest never one among them. There were others fringe players like myself probably equally shy and aloof one who had huge stashes of comics which i would either borrow or steal and furtively read between the covers of my school texts (until my brother discovered them and tore them up). And we had so many characters not just from Enid Blyton (long before Golliwogs were decidedly racist) but Phantom, Mandrake, Tarzan, Casper, Sad Sack, Spooky, Archie, Hot Stuff, Little Lotta, Blondie, Asterix and Tin Tin, pixies, gnomes, elves, leprechauns, fairies, and those from Chandamama and Amar Chitra Katha all more valuable than greenbacks. As we grew older and rebelled as teens in our inimitable ways getting away to talk in whispers of taboos like sex or drinking or practicing bad words to be uttered with insouciance. I horrified my parents by becoming deeply religious and reading books not congenial for my age. The girls banded together in their own small groups, though the elder of them were seemingly distant probably imagining futures not yet upon our little minds. Many boys held their secret crushes and bated breath and silly tales and catcalls. Most of these children unlike myself and my brother and few others went to the same school Cardinal Gracias and i used to complain to God how unfair he was to me that not only these guys constantly play at home and in the compound but on the way to and fro and at school too. They carried their secrets together and i was privy to none of them. I wish it were a perfect idyll and alas it wasn't as domestic strife and violence was rife and children often huddled incomprehensibly as their elders swore or fought both at home and outside.

I grew to be uneasy and restless and I severed the already tenuous links with my cohort of children and came to see my new identity as some one different, serious about purpose and meaning and much prattle that alarmed my onlookers (and intrigued Mahesh Kamath to be my sole friend who like' Hobbes' would listen to my gibberish endlessly as we worked up being the Asiatic Society, Lalit Kala and Sahitya Akademi, Krishnamurthi Foundation all rolled into one). I wore conservative apparel like dhoties and kurtas while the rest sported torn jeans. I worried my parents no end with what they thought was the worst of both worlds. My migration to another state for my engineering studies cut loose all connections and probably helped me grow up unfettered by my own past for the better or the worse. On my return after many years it was never the same again and what was broken and torn could never be mended or stitched back. The compound was paved over and concrete poured around and prosperity converted much of what remained of the compound to a parking lot with a little strip pretentiously called Fulvari where they placed most unimaginatively a swing and slide that rusted into oblivion making tetanus stained gashes to children who ventured. Most of the sibling brothers had departed, they punctuated their routines with scheduled visits to parents that seem sometimes a solemn routine not always joyous or siblings, sometimes close some distant, some torn by rivalry some keeping up appearances. I was a stranger in my own home not just compound and fled to the solace of the unfamiliar. Decades later when my father persuaded me to return i came to see the trees grow older, ailing and in some cases decrepit or even dead. Each carefully treasured their memories of home and hearth that the compound foregrounded, the laughter and the tears secretly. They spoke of redevelopment in a tongue that i scarcely understood (or wished to understand); of swimming pools and swanky lots and whether they should have one or two parking spaces. They knew not the secrets of the compound or its million hiding places, of boughs that bore our weight without breaking, the secret signs and codes and the million ties that compound held our hands by in our mud smeared faces and slipping 'chuddies'.

Never again have i seen a train of such wonderful children so full of life and joy blessed by nature in her ample arms play again in that compound. I feel sorry and pity for children in the same compound who today seem to play sterile games restrained by their finery and upbringing to be the child nature wants them to be. The compound is now cut up by the developer. The walls are pulled down, the windows stripped of their happy faces and robbed of their memories. The trees forlorn and sad, the birds mournful. As i see the compound walled up with tin sheets i regret that the ringing shouts, of children will never bedeck the gardens and the grounds, never beckon us back again into that innocence and simplicity where there was much contentment. In the words of the poet

I feel like one who stands alone,

Some banquet hall deserted,

Whose lights have fled,

Whose garlands dead,

And all but he departed.

_________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

*My parents kept me from children who were rough

and who threw words like stones and who wore torn clothes.

Their thighs showed through rags. They ran in the street

And climbed cliffs and stripped by the country streams.

I feared more than tigers their muscles like iron

And their jerking hands and their knees tight on my arms.

I feared the salt coarse pointing of those boys

Who copied my lisp behind me on the road.

They were lithe, they sprang out behind hedges

Like dogs to bark at our world. They threw mud

And I looked another way, pretending to smile,

I longed to forgive them, yet they never smiled.

Stephen Spender

No comments:

Post a Comment