Rasadhwani

–Emotive Resonance or Rapture

A.

Srinivas Rao

“Raso vai saha. Rasam hyevayam labdhva anandi

bhavati” Yajur Veda, Taittiriya Upanishad 2.7 “For He indeed is Rasa, having obtained which, one attains

bliss”.

|

| Padmapani, Ajanta, 450-480CE |

Rasa is the axial concept of Indian aesthetics and so central is its position that commentators down the centuries “with

|

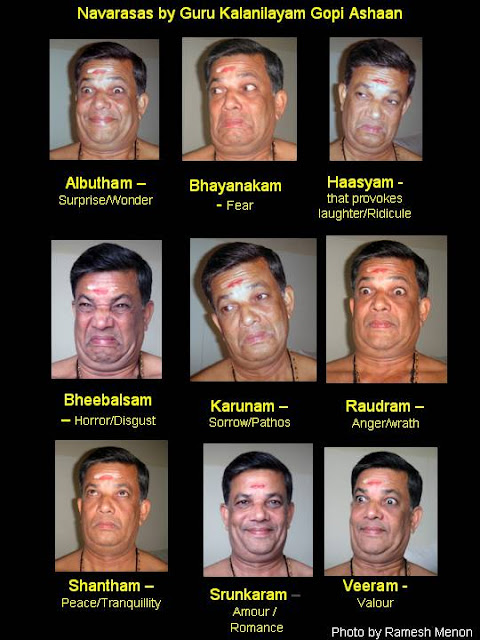

| Rasa abhinaya in Kathakali, Kalanilayan Gopi Ashan |

Theatre

was paradigmatic of all Indian art and was the wellspring of inspiration for

all art forms encompassing poetry, music, dance, painting etc. Bharata was its

original seer. To Bharata a dramatic performance was a play of emotions and the

successful manifestation of these on the stage was realised when the audience

relished or resonated (rasaasvadana)

within their own self the dominant emotional theme of the play. To invoke the

experience of rasa in the spectator

Bharata proposed breaking down the emotions into what he considered their

components. To do this he developed his psychology of bhavas or emotions and made these bhavas the basis of his theory. Bharata views bhavas as causal, “that which makes manifest” or that which brings

forth or makes aware a person’s mental state. However not all bhavas according to Bharata are mental

they also had physical complements. To begin with he proposed that emotional

states while transitory have differential levels of inertia. The dominant

emotion of a composition was to him the relatively permanent which he called as

stationary (Sthayi bhavas). He

believed that the dominant taste or flavour of a composition (rasa) emerges from these sthayi bhavas. He classified sthayi bhavas into eight kinds and held

that the dominant rasa in a

composition emerges from these eight inertial emotive states and thus has its

correspondence to each of these moods. Thus they form eight pairs of sthayibhava-rasa viz. pleasure (rati)-Erotic (sringara), laughter (hasa)-

Merriment (hasya), grief (shoka)-Compassion (karuna), anger (krodha)-Wrath

(raudra), enthusiasm (utsaha)-Heroism (vira), fear (bhaya)-Horrific

(bhayanaka), aversion (jugupsa)-Disgust (bhibhtsa), wonder (vismaya)-Amazement

(adbhuta). He further states that as

against the more fixed sthayi bhavas,

there are 33 relatively transient emotions based on psychological states of the

mind called vyabhicharibhava which

are supplements to the dominant emotion set by the sthayi bhava. These include indifference, exhaustion, doubt, envy,

infatuation, exertion, sloth, abjectness, anxiety, delusion, recollection,

constancy, modesty, alertness, pleasure, agitation, lethargy, arrogance,

dejection, zeal, languor, forgetfulness, sleep, awakening, impatience,

understanding, sickness, passion, death, fright, argument, dissimulation and

ferocity. To this rather exhaustive list Bharata added physical manifestations

of the above states he called as anubhavas

such as flustering, languorous movements etc. ; of these certain kinds of physical

manifestations were called sattvika

bhavas, eight of which he enumerated as stupefaction (stambha), perspiration (sveda),

horripilation-goose bumps (romancha),

stuttering (swarabhanga), tremor (vepathu), turning pale (vaivarnya), tears (ashru), nervous breakdown (pralaya).

Together with the sthayi, vyabhichari and sattvika bhavas this was a list of 49

states. He then discusses the situational factors or contingent conditions

under which these bhavas emerge which

he calls vibhavas. Vibhavas could be stimulating (alambana) or rather pertaining to the

person in respect of whom an emotion is being felt or excitatory (uddipana) i.e. the ambient environment,

season, landscape etc. Having thus made such elaborate classification Bharata

makes a proposition the “Rasa Sutra” that has been commented by scholars down

the centuries “tatra vibhava, anubhava,

vyabhicharabhava samyogat rasa nispattih” i.e. Rasa emerges from primary

emotions caused by their excitants, secondary manifestations of that emotion, and

the context or landscape (psychological and physical) where they are played

out. In other words, the vibhava, the

anubhava and vyabhicharabahva give rise to the dominant emotion or sthayi bhava which in turn makes

manifest the Rasa or sapience.

Over

time with social stratification becoming more rigid with their norms of ritual

purity, it was poetry and poetics and not theatre which was considered the

paradigmatic art by the scholarly class of Brahmins. The Holy Grail was now

“what is the soul of poetry”? Through the centuries that followed, rhetoricians

had a succession of answers each contesting the previous one. These were six

schools of thought (from 6th -11th century CE) or the six

points of departure (prasthana).

There was the school that held rhetoric as central to poetry (alamkaraprasthana). This school was

supported by the views of Bhamaha, Vamana, Udbhata and Rudrata. They maintained

that rhetorical devices were like an ornament to poetry raising the question of

whether it was an imposed beauty or intrinsic.

The next school was that of poetic quality (gunaprasthana) championed by Dandi

and maintained that poetry must have qualities like pun, clarity,

sweetness, vigour, poise, etc or even incandescence (kanti) and propriety (auchitya).

The next school was that of style in metrical composition (ritiprasthana) by Vamana where the merit of a poem was in the skill

over styles of metre like Gaudi,

Vaidarbhi and Panchali. The next

school of Kuntaka was that of indirect meaning (vakrotijivitaprasthana) which held that poetry hints that there is

an indirect meaning that is true than the one obvious. The next school was

called the dhwaniprasthana by

Anandavardhana and referred to poetry being more than the sum of parts like

rhetoric, metre, words, meaning etc. a whole with resonant levels of meaning

more than the one explicitly stated. Anandavardhana spoke of three kinds of dhvani, i.e. resonance of subject,

rhetoric and sapience (vastudhvani,

alankaradhvani and rasadhvani). This

last kind of dhvani ties up with the

last school of Rasa

|

| Abhinavagupta, frontispiece "Abhinavagupta" KC Pandey,1935 |

Most

of the scholars mentioned above seem to have been almost wholly Kashmiri

Brahmins, the prince of among them being Abhinavagupta (950-1020 CE) a polymath

of unrivalled genius. Abhinavagupta’s works are numerous and fall into three

principal categories Aesthetics, Tantra, and Kashmiri Saiva philosophy. His

commentary on Bharata’s Natyashastra called Abhinavabharati and his commentary

on Anandavardhana’s Dhvanyaloka called Lochana happen to be the grand synthesis

of aesthetic thought in India

Abhinava’s

bold conclusions were that Rasa was not

an object of knowledge, not the effect of a cause, not located in time though

impermanent and as an experience was revelatory i.e. neither direct nor

indirect, neither mundane nor supernal, nor indefinable. Rasa dissolves the

distinction between the knower and the known, it is whole and undivided with no

parts nor types, it is not cognition but a re-cognition, a revelation to

oneself of ones own depth, a form of self contemplation, akin to a magical

bloom (adbhutapushpavat), a wonder (chamatkara), full of intelligence, self

luminous beatitude (akhandaswaprakashanandachimaya)

and finally the twin brother of tasting the Absolute (brahmaswadasahodara).

|

| Ardhanariswara, Elephanta Caves, 5th-8th CE |

Abhinava’s

theory is called the notion of revelation (abhivyaktivada).

The cardinal process is the transmutation from the gross to subtle, the mundane

to transcendent, and individual to the universal. Abhinava took the ideas of

Anandavardhana’s dhvani or multiple

levels of resonance of meaning, or the power of suggestion (vyangya shakti). Anadavardhana maintained

that suggestive or evocative meaning (Dhvani)

is the essence of art. The indirect meaning of an art object penetrates the

superficial and resonates with multiple meanings without rejecting any.

Abhinava also creatively used Nayaka’s notion of a suppression of the

aesthete’s ego through a process of generalisation (sadharanikarana) and defined conclusively the process of revelation

of rasa. This transformation requires a prepared

aesthete, quiescent (vishranti) and

detached (samvit) mind both of the

artist and the aesthete. The aesthete (sahridaya)

is one who can identify with the subject, whose heart is sensitive and polished

(and not hardened by poring over dry metaphysical texts) and is capable of

complete identification with the object (tanmayibhava)

that distinguishes not experience of his own self from that of the

artist-protagonist and is responsive to suggestive revelation (abhivyakta). This capacity of unfettered identification (tanmayibhava) dissolves subject-object

consciousness, permits expansion of consciousness (chittavistra) and finds release in rasa. As the aesthete perceives the vibhavas, etc portrayed, she evokes within the sthayi bhava of the artist, identifies herself with the character’s

situation using her imagination (pratibha),

she identifies herself entirely (tanmayibhava)

with the character or art object leading to a suppression of one’s ego and

generalisation of the sthayi bhava

and experience (sadharanikarana).

This suppression of ego leads to an experience that is freed from the

inadequacies of one own self or that of the artist (vita-vighna, pratiya grahyata)

and reveals the depth of one’s own self, tasting bliss of an undivided (akhanda) rasa. This is the state of rasa,

an ineffable rapture. Abhinavagupta was a Kashmiri Saiva, a school which

conceptually distinguished two modes of consciousness that is unitary: visranti

where consciousness turns inward and abides in its own luminosity; vimarsha

where consciousness expands outward to embrace objects. This dualism in unity is

portrayed by the Ardhanariswara where Brahman or the absolute is not just self

luminous as Siva but also self conscious as Parvati looking into a mirror.

|

| Maheshamurti Siva, Elephanta Caves 5th -8th CE |

After

Abhinava a few more followed to comment on the essence of literature like Mammatha,

in Kavyaprakasa, Vishwanatha of Sahitya Darpan and Jagannatha in Rasagangadhara but none would equal the

zenith that Abhinava scaled. Indian intellectual output after this period

declines perceptibly owing to varied causes both external and internal and

became effete and weak to be re-vivified by the Mughals and their unique synthesis

and finally the domination by the West.

No comments:

Post a Comment